10 images that will transport you through Saint-Henri’s rich history

Travel back in time thanks to striking archive images that retrace the neighbourhood’s rich journey from small village to industrial hub.

Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. Fonds Conrad Poirier, BAnQ, P48,S1,P11917.

The building that hosts Entrepôts Dominion has stood proudly on the edge of the Lachine Canal since 1899.

In the above photograph, which dates back to 1945, it appears in the background, on the other side of the train tracks, as Canadian writer Gabrielle Roy poses with a group of Saint-Henri children. The photo was taken at the intersection of Saint-Ambroise and Saint-Ferdinand, in front of one of the buildings of the Dominion Textile Company. The neighbourhood sure has changed a lot since then, but the spot is easily recognizable — even today — thanks to the imposing silhouette of Entrepôts Dominion.

This massive brick building is just one of many architectural landmarks that have resisted the passage of time. Other mythical buildings such as Atwater Market, the Saint-Henri fire station, and Château Saint-Ambroise (formerly part of the same factory complex as Entrepôts Dominion) are integral parts of the Saint-Henri cityscape.

Through fascinating archive images, get ready to immerse yourself in the past lives of Saint-Henri.

Saint-Henri-des-Tanneries

Around 1685, Jean Talon (a name that surely rings a bell for most Montrealers!) looked to establish new industries, including tanneries, in Nouvelle-France to support the colony. But tanneries had to be constructed near water — and outside of the city walls on account of the strong smells they produce. So a handful of tanners set up on the banks of Ruisseau Glen, a small stream that used to run on the current intersection of Saint-Jacques and De Courcelle.

A view of “Tanneries des Rolland” (Saint-Henri’s former name), near Ruisseau Glen. Watercolour by James Duncan – Archives de la Ville de Montréal, BM99-1_01-p-258, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

Saint-Henri was once nestled in the countryside. Today, from Place-Saint-Henri metro station, a commuter can reach downtown in about ten minutes. Back then, however, it took half a day to make the trip between Saint-Henri and Montreal!

At the time, the village wasn’t yet called Saint-Henri and was home to only about a dozen families. But when a small chapel was erected and a pastoral school opened in its basement, the community soon started growing steadily. By 1825, the village’s population had reached 450 people according to that year’s census.

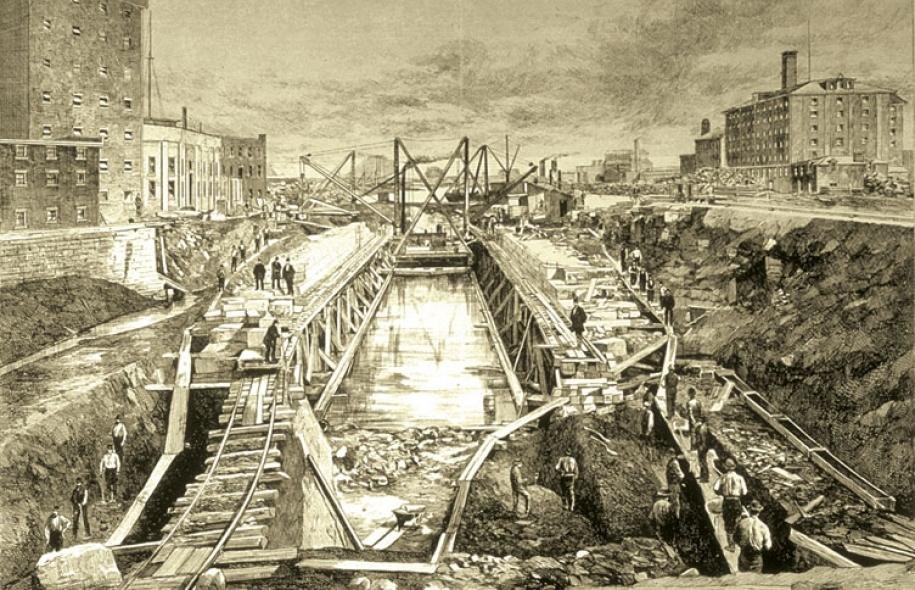

The Lachine Canal and its industries

That same year, the Lachine Canal was dug. Along with the arrival of the railroad in 1847, it greatly contributed to the industrial development of the area. (So much so, in fact, that it was widened twice in subsequent years to accommodate the growth of the Saint-Lawrence’s steamboats.) By the mid-19th century, Saint-Henri had become an industrial hub, not just for the Montreal area, but for all of Canada.

Lachine canal enlargement. Work at the St. Gabriel Locks, under Messrs. Loss & McRae, tiré d’une photographie de Henderson, Canadian Illustrated News, vol. XVI, no 22, 1er décembre 1877, p. 344-345.

From 1881 to 1901, the Saint-Henri population more than tripled, going from 6,400 to 21,000 residents. This unprecedented demographic boom can largely be attributed to the arrival of the Merchant Manufacturing Company, a cotton mill that set up shop on Saint-Ambroise Street. At the time, Saint-Henri still looked a lot like a small country village, but the various industries that were slowly settling alongside the canal would soon have a massive impact on the urbanization process.

L’intersection des rues Notre-Dame et Saint-Philippe, Saint-Henri, 1905 (Archives de l'ACHF, Fonds P042, Musée ferroviaire Saint-Constant, Québec)

Between 1882 and 1899, the Merchants erected several towering buildings along the canal to accommodate its factory and warehouses (the very same that host Entrepôts Dominion today!). A few years later, in 1905, the Merchants was acquired by the Dominion Textile Company, which alone employed no fewer than 3,000 workers.

Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec. Dominion Textile Co. 1910. https://collections.banq.qc.ca/ark:/52327/2083197

That same year, Saint-Henri was officially annexed to the City of Montreal. Notre-Dame Street quickly became the epicentre of this working-class neighbourhood, in large part due to its proximity to the Canal and the railroad. The photograph below shows the façades of the stores located near Place Saint-Henri, an intersection that looks quite different today.

Saint-Henri. 4041-4039 rue Notre-Dame Ouest. 1929. VM166-D1901-30-021. Archives de la Ville de Montréal.

Beaudoin Street, which stretches out from the Canal all the way to Notre-Dame, has also changed quite a bit. In this photo dating back to 1945, we can see the old wooden façades of its houses, which have since been replaced by brick.

Bibliothèque et archives nationales du Québec. Feature. Rue Beaudoin: St. Henri - P48S1P11908

Of course, the Dominion Textile Company wasn’t the only factory to settle in the neighbourhood and help shape the Saint-Henri we know today. Around the same time, in 1907, Imperial Tobacco opened a factory on Saint-Antoine. A few years later, in 1919, they were joined by the Simmons Bedding Company.

Ludger Lemieux leaves a permanent mark

The Great Depression of 1929 hit Saint-Henri industries hard. Nevertheless, the 1930s were an important time for the neighbourhood, as many architectural landmarks stood up from the ground, thanks to the significant contributions of architect Ludger Lemieux.

Born in the Eastern Townships, Ludger Lemieux studied architecture at McGill University. In 1931, he founded the firm Ludger & Paul M. Lemieux alongside his son Paul Marie. Together, they designed buildings all over the province, notably in Saint-Henri.

As early as 1912, Lemieux had contributed to Saint-Henri’s built heritage by designing the Saint-Irénée church, located steps away from the Lionel-Groulx metro station today. But in the ’30s, Ludger Lemieux hit two consecutive home runs, first with the Saint-Henri fire station (1930) and then with the incomparable Atwater Market (1933).

It goes without saying that the neighbourhood wouldn’t look the same today without his unique touch.

Marché Atwater. - [Après 1933]. [193-]. Fonds Camilien Houde. P146-2-2-D2-P015. Archives de la Ville de Montréal.

Gabrielle Roy: Saint-Henri enters posterity

In 1945, Canadian writer and journalist Gabrielle Roy published a now-famous literary masterpiece, Bonheur d’occasion, set in the tough working-class reality of Saint-Henri. She writes with a dark lucidity about the factories and warehouses that border the canal, the sounds of the trains that cross the tracks on Saint-Ambroise, and the bustling nightlife of Notre-Dame Street.

The poignantly realistic novel soon became a staple of Canadian literature and, with it, Saint-Henri made history.

In the photograph below, taken on the year of Bonheur d’occasion’s release, Gabrielle Roy (on the right, leaning against the barrier) watches the train go by. In front of her, on the other side of the tracks, stand the buildings of the Dominion Textile Company.

Feature. Engine Crossing Street : St. Henri. La locomotive et le wagon de queue passent sur la voie ferrée devant Gabrielle Roy, 29 août 1945. BAnQ Vieux-Montréal (P48,S1,P11912). Conrad Poirier

Today, commuters going through Place-Saint-Henri metro station can see the words “Bonheur d’occasion” embedded in the station’s brick wall, paying homage to the unforgettable novel of one of the great Canadian authors.

Decline and rebirth

The Dominion Textile Company continued to thrive until the 1960s, but the closure of the Lachine Canal in 1970 was a death sentence for many of the factories located on its shores. The Dominion was no exception.

The Saint-Ambroise Street building was then bought by Coleco, a toy manufacturer. During its glory days, the business employed 800 people in its Saint-Henri factory, where it assembled Atari’s famous Pong console, among other things. Unfortunately, Coleco filed for bankruptcy in 1989 and the building was left empty and abandoned.

It wasn’t until 2006 that advertising agency Bos bought the derelict warehouse and initiated a complete revitalization. The renowned architect Luc Laporte led the project, with the firm intention of highlighting the architectural elements that served as the hallmark of this industrial space. The brick walls and iron beams are there to stay!

Today, the building is home to a unique multifunctional space with a name that lives up to the building’s rich past: Entrepôts Dominion (the Dominion warehouses).